In his short story collection, “Twice-Told Tales,” Nathaniel Hawthorne brilliantly revisited the ancient myth of Theseus and the labyrinth. For those unfamiliar with this tale (which should apply to at least half the audience of a Pixar film in 2016) Theseus was a Greek hero imprisoned by Minos, the King of Crete, in an impossibly complex maze from which nobody had ever escaped. Fortunately, Theseus had won the love of Minos’ daughter Ariadne. The young princess gave her lover the keys to navigate the gordian passages and emerge on the other side unscathed.

Like many writers of his time, Hawthorne was obsessed with finding modern significance in older stories. His take on history’s first great prison break updated the material for an audience that was beginning to struggle with concepts of individuality and mental health that were foreign to the ancient world. In the reheated version, the labyrinth is not merely physically complex. It has a magical effect on its captives, blinding them to reality and imprinting untold anxieties and invisible rules on their brains until eventually they went insane. This will be familiar to anyone who has ever walked downtown in a large city during rush hour.

In this version of the story, Ariadne didn’t simply hand Theseus a map. She also gave him a long thread, holding the other end herself. Every few minutes she would tug on this thread, and Theseus–whose mind was constantly wandering and threatening to give up–would remember his lover and his mission and continue soldiering on. It’s an elegant metaphor for the way love serves as a compass in a modern world where a person’s greatest enemies are often the voices inside their own head.

Pixar, America’s last bastion of innocence, has also been revisiting their twice-told tales recently. When they were trailblazing outsiders, John Lasseter’s brain trust dismissed the idea of (non-Toy Story) sequels as pointless cash grabs and exploitation of audiences’ desire for familiarity. Now in their third decade and decidedly “the establishment,” the world’s most popular animation studio has eased up on that rule. The results have been uneven, ranging from classic (Toy Story 3) to acceptable (Monsters University) to “sign of the apocalypse”-level terrible (Cars 2) with Incredibles 2 and Toy Story 4 rumored to be on the way.

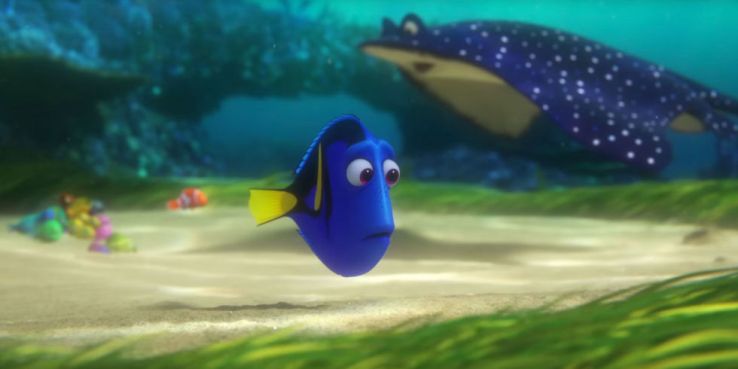

Finding Dory fits easily in the Classic camp. It might even be the best sequel Pixar has ever produced (which you will know, if you’ve seen Toy Story 2, is a very, very tall order). This time the protagonist is Dory, the memory-deficient blue tang who played sidekick to clownfish Marlin in Finding Nemo. I’ll admit that the idea of structuring a whole film around a one-joke comic relief character sounds like a bad idea. Fortunately, director Andrew Stanton (Finding Nemo, Wall-E) remembers the inherent sadness in the character that audiences from 13 years ago may have forgotten.

Marlin’s cross-ocean odyssey (more Greek stuff, one might observe) was lined with brutality and sadness just subtle enough to sneak past younger viewers. Dory was one of billions of fish alone with a disease and no way to help herself, like a dolphin with a plastic can holder wrapped around its nose. Her mental illness was great for getting the kids to laugh, but the character voiced by Ellen DeGeneres always had a whole lot more going on. If you revisit the movie before seeing its sequel, you may remember how heartbreaking it is when Dory begs Marlin not to leave her in his despair because she doesn’t want to forget anymore.

So now, thanks to Pixar’s absolute refusal to coddle their youngest viewers, we get to see a wide-eyed (like, excessively wide-eyed, even for an animated baby fish in a children’s film), optimistic child version of Dory torn away from her family and lost in a vast, unsympathetic ocean. Hey kids, here’s what growing up actually feels like. Good luck.

Thankfully (because I don’t think I could have handled much more of that lost child thing without completely losing it) Dory has found a slightly happier place when the story actually kicks in. She now lives next door to Marlin and Nemo and is accepted (though begrudgingly) as part of their community. Her memory problems are still an issue. She wakes up her neighbors over and over in the middle of the night and distracts the children of Nemo’s school. Likewise, her call to adventure isn’t quite as desperate as Marlin’s attempts to save his one surviving child. Instead, she remembers her original mission of trying to find her parents, along with some idea of where they might be.

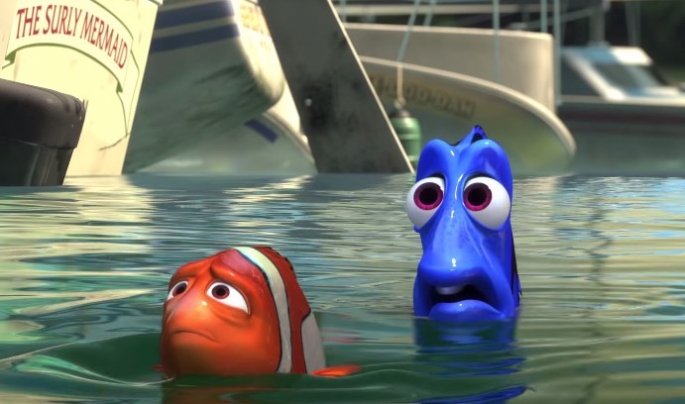

The target audience of Finding Nemo was adults (particularly young parents) in 2003. Marlin was a widower trying to protect his only child in a world becoming scarier and less predictable every day. He needed to learn to trust and explore again and do away with old prejudices about outsiders. Dory has more in common with the young adults of 2016. She is single, unmarried (we’re still left guessing about what her relationship with Marlin actually entails) and plagued by problems of a vaguer, more psychological bent. The world is telling her to simply fit in and make peace with the way things are. “The only reason to travel across the ocean is so you never have to do it again,” Marlin insists.

But Dory is better at trusting her instincts because they’re all she has to rely on; and those instincts tell her there are answers somewhere out there if she only looks hard enough. At the end of this journey is not some great extroverted trek across the world but a manic heist inside an Oceanographic Institute that essentially amounts to fish therapy. Yes, fellow Millennials, Pixar is still making movies exclusively for us. Aren’t we special?

Along the way, Dory learns to trust her instincts and embrace her positive qualities. Children will see this as yet another story about “believing in yourself,” but to an older, more jaded audience, there’s some pretty loaded subtext. All of a sudden I’m wondering if Dory’s plight has always been a metaphor for the way the internet has stunted the memory of children of the nineties and made self-discipline far more difficult, while also preserving their sense of whimsy, intuition, and optimism far longer than their parents.

This is also where the labyrinth comes back into play. In her quest for home, Dory keeps recalling stray memories from her past and messages her parents imparted before she lost them. Her approach seems insane compared to Marlin’s pragmatism, but in the end it’s the only way to navigate a problem far more complicated than (if nowhere near as dramatic as) finding one child.

Dory also quickly realizes that many other animals have their own quirky, impossible problems. There is a seven-legged octopus (or septopus, as Dory calls him) so afraid of being released into the ocean that he’s trying to hitch a ride to a Cleveland aquarium instead. There are sea lions who obsess over their status napping on a single rock. There is a blank-eyed bird that can only hear someone if they look it in the eyes and mimick its call several times. Two of Dory’s childhood friends include a nearsighted whale shark and a beluga whale whose sonar is blocked.

The voice of Sigourney Weaver frequently reminds visitors that the goal of the Institute is rehabilitation, then release. However the reality of their treatment and display for callous audiences is far more Darwinian. Some animals deemed beyond help eventually become fodder for aquariums and petting pools. These creatures seem lost in their own personal labyrinths, and many of them need the kind of openness and optimism that comes very naturally to Dory. Just like Dory’s friends serve as her connecting thread when she’s facing her darkest fears (that would be following simple directions like “take two lefts”), a self-reliant Dory is equipped to serve as their anchor as well.

One of the reasons Pixar remains a force in the movie world, not just financially but also artistically, is their insistence on viewing their movies as a conversation with a specific audience. The young children who first watched Toy Story are the same ones who were teenagers when Finding Nemo came out, college students when Toy Story 3 came out, and now adults in 2016. Their movies continue to address this original audience and reassure them that those timeless lessons about love and, yes, believing in yourself, still apply even when you’re approaching 30.

Their message to the Marlins of the world: learn to see these internal struggles as a fight for the same sense of home and connectedness you feel for your children. Their lesson to the Dories of the world: keep trusting your instincts and fighting the battles you need to fight, no matter how many op-eds call you selfish and entitled. The lessons your parents imparted to make you self-reliant still apply, even if the context has gotten muddy. The world needs you, not someone else’s idea of you, whether they care to admit it or not.

In other words, just keep swimming.