Part 1 — Bootstraps

At a distance thing looked better than ever. I knew they did. I had worked hard to make them look that way.

I had just been promoted to supervisor at work and received a two dollar an hour pay raise. I was writing for a local website. It didn’t pay, but I was getting exciting networking opportunities. A few of my articles had earned me a decent following. I had been living for almost a year in my own apartment. I was planning an ambitious production of a little-known William Shakespeare play, with a cast and crew locked down and a good venue booked.

It had been years since I was first aware of my severe depression and anxiety; since I first started going three or four days without sleep, sometimes sleeping 20 or 22 hours instead; since I fell apart the last year of college and departed one class short of graduation; since I laid on the floors of friends apartments staring at ceilings and walls because my emotions were racing so quickly I could do nothing else; since I failed to hold a job and moved into my parents’ basement; since I made a manic return to school which I self-sabotaged in an absurd manic episode; since I drove away dozens of friends, not understanding my own behavior, some calling me a toxic personality; even since I stumbled alone through Minneapolis living in a house for recently released prison inmates, regularly getting into car accidents, making myself throw up with anxiety, hoping nobody discovered my apartment and car were covered in trash, barely holding it all together.

But now things looked okay. At family gatherings I could tell people what I was doing with my life. I could be proud.

I had worked more than 52 hours a week, sometimes up to 70 or 85 hours, for over a year to get to this place. I had made a few new friends. I started dating again. I lost weight. I directed a play for the Fringe Festival in August. The show hadn’t gone especially well, but it was a far cry from the Fitzgeraldian tragedy I had been living up to that point.

Part 2 — It’s an Awful Sound When You Hit the Ground

The lie I had preserved for over a year, thankfully, came crashing down on my head one cold day in February.

It started with a physical illness; the kind it’s easier to admit you have out loud. I hadn’t taken a day off work for my health since I moved back to Minnesota, but with the heat in my apartment at ninety degrees, wrapped in two comforters, and shivering like a dead man, I found it necessary to take a week off work.

Lying there in bed, surrounded by the same trash and unwashed sheets and (I could faintly detect) the smell of mold, I wondered melodramatically if I died, how long would it take for anyone to notice? This was as much a practical question as a maudlin one. A distance had formed between myself and everyone who knew me. I blamed all of them for its creation, despite my being the common denominator. I avoided all phone calls, especially from my family. I had driven all my friends away. I hadn’t seen any of them in over a month.

At the end of the week, just as I was starting to feel better, I treated myself to a movie at the dollar theater in Hopkins. During the trailers I reached into my pocket and discovered my phone was gone. I looked all over the theater, traced my steps back to my car, then tore the car apart looking. The phone was nowhere. I knew I wasn’t going to find it. This used to happen to me all the time, when I was a kid stretching into my earliest years in college. It hadn’t happened for a while though.

I went back inside to finish the movie and then spent three hours trying to get my old Kindle charged and connected to internet to cancel my phone and make arrangements.

Both of these first two problems should have been tolerable, but there was a greater fear that made them disastrous. I didn’t want anyone to look too closely at my life. Viewed through a magnifying glass, my steady improvement could be seen more clearly as rapid deterioration. For every step forward, I became less human. I was living an adaptation of Kafka’s Metamorphosis, hiding in the back corner of a dark room, thoughtless and blank, long past the point of remembering why I was there or how I intended to escape. I felt a deep, animalistic panic about the idea of anyone stumbling upon my hidden squalor.

The final blow to my facade was struck the very next day. I hadn’t checked the oil in my car in months, and driving down highway 169 I heard a weird sound in my engine. Within a mile my car was violently lurching. A hundred yards after that it was dead on a busy highway with no shoulder. Also, I had no phone.

In the cold February wind I stepped out and began flagging people down. All I was thinking was how angry I was, and how afraid I was that someone might look inside my car, see the food lying in the passenger seat, smell the cigarette smoke I had been hiding for years, notice how low my bank account had fallen despite all my work, realize it was all my fault.

It took two hours for a snow plow to pull over and offer to call the police. For two hours, in the cold, still sniffling, I stood in front of my car, waving my arms wildly, getting the attention of distracted drivers who came a little too close for comfort. They towed me to an auto body shop. The mechanic tried not to stare at the disaster of torn books and fast food bags and dirty clothes, passing a look midway between pity and embarrassment. The engine was dead, he said, and it would cost more than the total cost of the vehicle to repair it. I left the car, never to see it again.

The bus didn’t leave early enough for me to make my new job, and I had promised my parents I had plenty of money, so I took a rental car to work for the next two weeks. By the end of that period my account was overdrafted by nearly 500 dollars. I avoided the emails from the venue for my play, as well as my editor who wondered why I was skipping out on assignments. If anyone asked, everything was fine. Small problems don’t cripple big people. I was going to overcome all of this.

After work every day I crawled into bed and slept around 14 hours. I hated myself for my weakness, my laziness, my sloppiness. Phone calls kept ringing. I kept ignoring them. My voicemail filled up and I deleted each new entry without listening. I tried watching movies, but that was too stressful. For three days I rewatched the same five episodes Buffy the Vampire Slayer over and over. If you had asked me immediately following an episode what I had watched, I probably couldn’t have told you. In fact, whole weeks would go by during which I couldn’t recall a single detail. The very idea of forming words in my mind became exhausting.

Just for fun one night I decided to try writing a Buffy episode in my head to bone up on story structure. I fell asleep before I was able to muster even one sentence.

I was just fine, thank you for asking.

Part 3 — Epiphany

Depression is a kind of insanity, and therefore it’s hard to explain in sane terms. Part of me was desperate and scared. Part of me also believed I was fine and I just needed to get over myself. With benefit of hindsight, I hadn’t been fine in a very long time–I started exhibiting many of these symptoms in early childhood–so I didn’t have much for comparison.

Often when severely depressed I’ve found thoughts and feelings escaping their anxious cages with seemingly no ties at all to anything I’m doing or feeling on the surface. Sometimes I would burst out crying for no apparent reason. Other times I would write about trees for an hour, then realize I had actually written about a friend who hadn’t called me back, or a task I was afraid of, or suicide. I was trying to send myself signals that I was incapable of receiving.

When my doctor asked me if my Prozac was working, I said possibly. We agreed it might be a good idea to double up my dosage. I told him nothing about my life up to that point. I didn’t want to complain. It seemed pointless.

The Prozac only helped me get to work each day. It made my head swim and my problems seem far away, but still my brain was unable to form words. This was a far cry from the Ryan who had once won contests with his writing, who took and passed genius tests as a child.

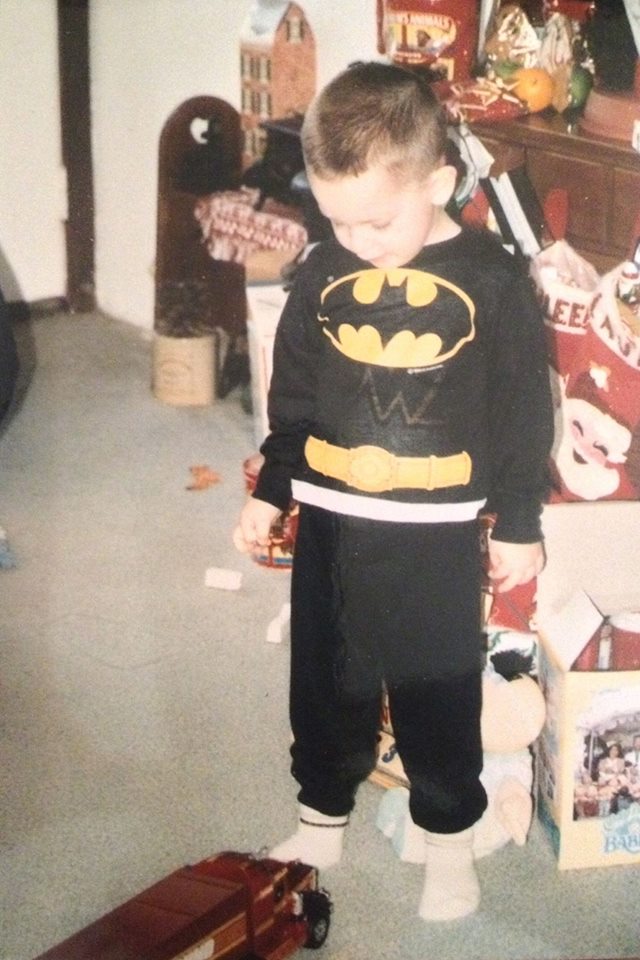

This was the other Ryan–the one who, at the exact same time as a child, was also placed in the special needs program because he lost all his assignments, accidentally wrote on his forehead, wandered the house late at night worrying until he made himself throw up, and seemed lost in invisible, fanciful dramas nobody else was privy to.

I started drinking heavily, looking for whatever relief I could find to recharge for the next day. There is no paid sick leave for mental health. If I committed myself or sought a drastic solution, I could wind up broke and living with my parents again, possibly for good. I held on, just barely, for the next month. I drank more, finding the loss of inhibitions exhilarating. I started realizing that, while inebriated, I could make plans and speak honestly with myself in ways I couldn’t crippled by anxiety. I started recording these thoughts so I could listen to them the next day.

One night I went too far, which just happened to be far enough. It began with tears. I was crying uncontrollably. My hands were shaking. My room was dark. I was too anxious to even watch TV. I couldn’t bear the thought of living another day. The alcohol gave me just enough perspective to see I hadn’t been well for years, and to see all my actions as a slow, helpless decline that could only have ended up here. Even now, with the benefit of perspective, I know that was true.

I decided to try a game. In my head I was going to mentally chart a path to happiness, one that began with me, drunk, sitting on the couch. I would create a strong mental image of what I wanted and how I planned to obtain it, and use it as my light at the end of a tunnel. I thought about filmmaking, my original childhood dream. I tried a version of the story where I fell in love. In every situation, I couldn’t get beyond the first couple steps. I began realizing that my irrational anxiety, calibrated incorrectly by my broken brain, had attached itself to even my happiest memories. My stomach lurched even at the thought of love and fulfillment. At times my whole body would shut down and despite the fact that I had slept plenty and it was the middle of the day, I would pass out while trying to think about these things.

I’ve never been a drug abuser. I don’t judge those who do it safely. It’s just never been my thing. But I was scared of myself, and the idea of ending it all was becoming just too tempting. I had realized how easy, how natural it was to slip off to sleep; thought how a bottle of sleeping pills might just make it permanent.

I wasn’t quite ready for that yet. I thought, what else can I try that I haven’t thought of yet? I recalled one night, years earlier, when I took some adderall with alcohol. I had felt invincible. I needed to feel invincible to conquer this. So that night I downed a whole bottle of whiskey and a couple pills. Do not regularly do this. It’s a very bad idea. It is, however, a better idea than a whole bottle of sleeping pills.

I blacked out, but not before I turned on my tape recorder. When I woke up, head tilted up toward the ceiling, my tape recorder had been running for almost six hours.

I turned it on and listened.

For the first few minutes I fumbled carelessly with words. I could vaguely recall what I had said during this part. But then began the parts I couldn’t remember. The effect was, in the most literal sense of the word, life-changing.

Just to be clear, again, I’m not advocating for drug abuse as a solution to depression. There is a good chance it can cause serious damage. My circumstances were singular and unique, and I know they’re probably not repeatable. However they are my honest circumstances, and I cannot change them.

I heard my voice change from desperate and lethargic to calm and hopeful. It began, “Ryan, you’re going to know deep down this is true. Right now I’m wasted, but even in this state I’m more sane than you are.”

From there I took the problems I had been facing; questions I had been asking myself for years; paradoxes I had tried to solve in short stories and plays; and one by one I calmly and rationally explained them to myself. “You’re trying so hard to be normal. Doesn’t that seem weird to you? How much do you read? How often do you work? How many of your problems do you face head on and still you can’t get by? Don’t you think maybe there’s a problem and maybe you don’t deserve it?”

I recalled a relationship from a year earlier (or the closest I had gotten to a relationship in a long time). We had gone on a few dates. At times there was a real connection. On the night of the fourth date, she came over to my place and we watched a movie. We started kissing after the movie was over, but then, suddenly, without warning, she stood up and said she had to go. I never heard from her again.

I explained the situation to myself in a way that didn’t end with, “You’re cursed and nobody will ever love you.” The way I was telling it now, I had been unable to feel any of the things she was feeling. My every decision, every movement was wrong, because I was not drawing from the source of hope and passion and, yes, lust, that she was. Most people, somewhere inside, take this connection for granted. I didn’t have it.

I remembered a movie I had written years earlier. I told myself it was really about me; whereas, when I made it, I told everyone including myself that it was some pointless grand philosophical treatise on some meaningless subject or other. It was really about me, alone in my apartment, learning that life scared and alone isn’t worth living, building up the courage to venture out and engage the world on its own terms. Some part of my brain so feared this idea that I was unable to look at it directly, yet still every scene followed that through-line and some part of me knew what I was doing.

I described in beautiful detail the love I felt for the people in my life. I remembered times I had noticed they were sad, but didn’t know what to do. I remembered things they said–how clearly they wanted me to give them some part of myself–how I had been totally unable to do that.

Nothing I was saying sounded ridiculous. All of it rang true. Somewhere inside me was this smart, loving, hopeful person. He was drowning, but he wasn’t dead yet. And it wasn’t all his fault.

I continued like this for six hours, eventually reaching this conclusion: “Deep down you know something is wrong, but you won’t trust your intuition. You fight so hard to convince people you’re okay, but have you ever once really believed you wanted to succeed? It’s okay to want to get better. It’s okay to take care of yourself for a while until you do.”

My studio apartment felt more silent than it had since I moved in. I was held in rapt attention, hanging on every world like I hadn’t in half a decade. Instead of the massive hangover I had expected, I felt an inner peace like one I hadn’t known since childhood. I felt like I had just awakened from a bad dream.

Part 4 — Getting Better

I swear this next part is true. It’s the truest thing I have ever experienced. If I hadn’t lived it, I wouldn’t believe it was possible. I wouldn’t have believed anyone else if they said they had experienced it.

Something was different. It was very, very different. I knew this alone in my apartment. I knew it when I walked outside. I knew it talking to a coworker in the parking lot. A weight had been lifted. Listening to a song before bed, I felt my emotions rise and fall with the music. It was so beautiful I cried (stark sober this time). I hadn’t really heard music in years. My attention was now able to engage what I looked at without attaching the echoes of myriad embarrassments and failures long forgotten, without being weighed down by a sluggish spirit that just couldn’t be bothered.

Over the next few weeks I felt an explosion of motivation without any anxiety. I cleaned my car and apartment. I returned library books that were years overdue. I got back in touch with friends and family. I started filling out applications for grad school. I had an out of body experience reading Walt Whitman aloud. My mind naturally and effortlessly attached itself to ideas and plans and the entire universe had never before seemed so fascinating, so full of promise.

When speaking to people, I found myself listening and wondering what they needed, rather than desperately wondering what they wanted from me. I started writing again, for the first time in ages, and it was easily the best work I had ever done. I had been manic before, but this was different. Mania is selfish. You are powered by irrational desires that develop internally. This was a heightened awareness, an engagement with the world based on feeling. I was connected to everyone and everything in ways I had never been aware of before. Something happened, and then I felt it. Now I could mourn with those who mourned, rejoice with those who rejoiced. It felt like the most incredible thing in the world.

All the things I learned in school, all the reading I had done, all the observations I had made around other people as an adult were suddenly accessible. I felt a deep intuition that guided me to a stronger connection with those who, just a week earlier, I thought I might never see again. As many friends and family members commented, I was like a new person.

From a distance, I could also see the wreckage of my past life. How foreign and alien my languishing thoughts seemed in the cold light of day. I wondered how I could ever have fallen into that trap and promised myself there was no going back.

With my newfound awareness, I also began scheduling appointments with a therapist. I wasn’t so delusional to think I would never need help again. I applied for new jobs, realizing I had no intention of spending my whole life as a security guard. Filling out job applications (much like doing the dishes and the laundry, going to the bank, talking on the phone) suddenly seemed easy. Everything that had defined my life for almost a decade felt like a cruel joke.

For the first few days all I felt was an intense sense of relief. Then I began remembering events from the past few years–relationships, achievements, even books and poems I had read. I was flooded with a warm sense of connection to the world. So much good and beauty was filling up the spaces fear and hopelessness had once occupied.

Most importantly, I no longer hated myself. I could see I was always working to become this person, that this person wanted to help people, wanted to carry his own weight in the world, and expended an abnormal amount of effort to get there.

After a couple meetings with my therapist, she said she believed about 80% of people with my severity of depression who go untreated are homeless. I started crying.

Part 5 — Glory Fades

The next month was the happiest of my life. Nothing exceptional happened. I felt wind and sun, read poetry (I realized that I hadn’t really understood poetry until that very moment). I came up with a dozen great ideas for new writing projects. I thought of half a dozen subjects I wanted to study. The fascination I once felt, had feigned in absence, had returned; and, because I never once abandoned it, even in the absence of all feeling, I was able to pick up right where I left off. I started a book club with my brother and sister, and made plans to just meet up and talk with my estranged friends.

Selectively, when the moment was right, I told people my story. In many cases they looked relieved, as though they had been worried about me and I was saying something they had wanted to hear for a long time. I felt loved and cared for in ways I had never before been capable of feeling.

The anxiety was the first thing to return.

I was having a conversation with my family after my brother’s graduation. There was nothing particularly notable about the conversation. We weren’t fighting. But that irrational fear that had clouded my every conversation since I was a child flickered for a moment.

I knew it distinctly. And because I had hoped it would be gone forever, I panicked. I asked to leave, walked outside to get some fresh air, and repeated a few of the strategies my therapist had taught me. I tried square breathing, creating a personal history, meditation, then ultimately locked myself in my brother’s room and read a book.

The episode passed.

A few days later it returned again. When I was at my worst in years past, I would fear calling someone I had known for eight years by their name, wondering if I was on a first name basis with them or whether I might get the name wrong, even if they were my best friend. Almost anything anyone could worry about in any circumstance, I worried about in every circumstance. And since my epiphany, I knew that those people had tried to care about me, but every time they looked into my eyes they saw I was still treating them like a stranger. I was neurologically incapable of familiarity–a black hole that desperately sucked the warmth from others, giving none back, not even keeping any for itself.

I promised myself I couldn’t return to this. I felt that, whatever control I had, I would fight with all my strength never to go back to where I was. I called my therapist’s office phone and left a voicemail. “I need to see you as soon as possible. When can I schedule another appointment?”

I wasn’t going back. I couldn’t.

Slowly I went back.

The book club I had started with my brother and sister, for which I had planned a dozen activities, began to feel like an exhausting and impossible task. I would spend all day reading, but the ideas that had flocked to my brain so easily were all gone. Every word now had some weight attached. Without even realizing, I would forget about it for two weeks at a time.

Things went on like this for a while. I kept doing all the things I had done while I felt well, but they were growing harder, less natural, and I felt like I was getting nowhere.

Then one Sunday evening I was driving, and suddenly, without any forethought, I shouted, “FUCK!” and started punching myself in a violent fit of anger. I pulled off to the side of the road, hands shaking, face beet red and sweating.

This new depression wasn’t like the last one. I didn’t feel lifeless. I felt angry and troubled. My helplessness was now twinged with fierce desperation and a knowledge of all I had to lose. While feeling anything seemed like an improvement, it made it harder to cope with the life I had managed to sustain during my last bout. I called off work one night because my head was racing so fast I couldn’t sleep, and I was making myself throw up. At work I would experience violent fits of anger–alternately, sometimes I had to take a break to go hide in the parking garage one building over and cry for fifteen minutes.

After nearly two months in paradise, I felt like I was on the return trip to hell. This fear and frustration gripped me and I started lashing out with any emotion I could hold onto. One day I would feel an almost uncontrollable rage, the next I could feel nothing at all. My therapist made an appointment for me to meet with a psychiatrist to get me on new prescriptions that could help with my symptoms, but the nearest available appointment was a month away and I could feel my hold on reality slipping.

By the time the appointment came, no remnant of that old inner peace remained. I had taken up reading, meditation, exercise, and better nutrition as coping mechanisms, but even these felt completely powerless to deal with the weight that was, daily, piling onto my every thought. I had learned to trust my intuition before. Now my intuition was screaming “Abandon ship!”

Part 6 — Triumphant

“i simply stopped

writing of truth

when my truths

no longer sounded

trimphant”

– Saul Williams

I am sitting in front of a computer screen. The words just barely hold my attention. Not every sentence is a winner, nor is it attached to an emotion, that way the best writers are able to accomplish. My sentence structures are much simpler and less revealing than my writing was a few years ago–than it was two months ago. In some ways the very act of writing makes me feel like a cripple, because I wind up comparing myself to the relative wellness of the past.

Still, I want to speak and words form in my head. I cannot remember the sheer hopelessness that crippled me not three months ago. I have not fallen that far.

I take my daily regimen of pills and feel some small improvement. My apartment is still clean, within reason. My car is also clean, within reason. I hung out with people last night and had a decent time, even if for long stretches of the night I felt nothing.

The other day I auditioned for a play. My leg shook so uncontrollably that twice I almost fell over. However, I held a conversation with the director that I couldn’t have managed last year. They were considering me for a small role in the ensemble. That had never happened before. Ultimately they went another direction, but they think my odds are good if I try again next time.

Yesterday the pills didn’t work. I paced anxiously, trying breathing and meditation. After six hours of effort I still hadn’t calmed down.

I went for a drive. I tried to focus on the warn sun against my skin, the cool breeze through the window gliding across my cheek. Still everything was racing and empty.

I grabbed a seat at a coffee shop, outside on the patio. While sipping a drink, I read some poetry. I heard a few lines in my head. They felt honest. I wrote them down, and continued. The overall poem was terrible, but the two lines were very good. When finished, I felt calmer, if not perfect. I was able to sleep that night.

Today I am not better, but I know what better looks like. I know it’s something I’m capable of. I know if I keep fighting I will get there someday. I know I really like the person waiting for me when I get there. I know people need him–there are things he can do in this world to help others and be necessary.

At my last session my therapist said, “Your goals are reasonable, but sometimes your timetable isn’t.”

She also looked me in the eyes and said, “I promise you will get better.”

If only one thing changed since February, it was still a big one: now I believe her.