Most of us are aware on some level that we walk in two worlds. There is the pragmatic world—school, work, putting food on the table and keeping a roof over our heads. Then there is the spiritual world. It doesn’t matter if you think of that literally or metaphorically. There are unconscious forces coursing through all of us that have nothing to do with how well we function in modern society. We are wired to survive in jungles, escape predators, and overcome fears that have nothing to do with sitting in a cubicle listening to Drake on Spotify.

From the broadest possible perspective, Buffy the Vampire Slayer is a TV show about this disconnect. The very title evokes the kind of kitsch our emotional needs can sometimes feel like. How many of us blush when we retrace a heated train of thought in the light of day? We want to be stable, constructive, serious people, and yet every night we encounter something that makes almost no sense in that context. This is the leap the original producers of Joss Whedon’s Buffy screenplay failed to capture. “How,” they asked, “could the story of a teenage girl named Buffy who kills vampires possibly be taken seriously.”

It’s not hard to see the TV show as his decisive, hundred hour reply.

We get jealous because our best friend is happy. We catch ourselves in the middle of an hour-long rant to our imaginary boss. We daydream about being rich and famous even when we can’t get up the gumption to take out the garbage. We get nostalgic for toys we lost when we were five years old. Our demons are (in most cases, I assume) metaphorical, but that doesn’t make them any less real. Running and hiding do us no good. Repressing often makes it worse. The only option is to confront our emotions and use them to our advantage. It takes an exceptional person to navigate that terrain while keeping their life from falling apart. It takes a slayer.

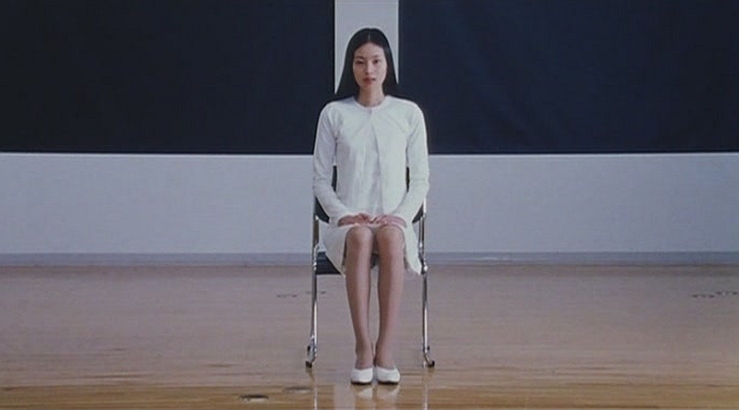

It’s also possible to view this pop culture behemoth in purely allegorical terms. When we first meet Buffy, she is a sophomore in high school dealing with raw, confusing emotions that seem very much like a horror film. Bullies become hyena people. Online boyfriends turn into internet demons. As Buffy grows older, the story becomes more complex. Her senior year is filled with rituals and fairy tales. Her first year of college is dominated by tales of metamorphosis and transformation. By the time she’s an adult, the demons have come to represent the forces of apathy and ennui. The result remains the same: the slayer faces a demon. The slayer slays it. The slayer remains a slayer.

This is one of the reasons (though definitely not the only one) why Buffy feels like such a personal journey to many of its fans. Take away the demons, the good guys and bad guys, the desperate plots to save the world, and you have the skeleton of a story that’s not unlike one we all go through. Buffy discovers intense emotions as a teenager. She figures out where she fits in this new world of feeling. She falls in love. She loses love. She learns to trust and relate to other people again. She develops opinions on social, political, and religious subjects. Her focus shifts to other people like her mother and her little sister.

And whether it’s a large penis-shaped snake demon or a punk rock vampire, she’s ready to face down her dark foils at every turn. We get to watch as someone navigates the world we remember all too well and behaves like a courageous, decent human being. The writers were not oblivious to how empowering this sort of thing can be.

Another reason why Buffy feels so ahead of its time is its pioneering use of the internet. The show doesn’t feel like a mere linear story. It feels like a dialog with the viewer. Other shows like Community feel the same way, and you’ll find they utilize many of the same techniques. Buffy writers frequented the boards of Whedonesque and other fan sites, gathering opinions and expectations offered up by the people who cared most. They didn’t always cater to the fans’ desires. Often it feels like characters in his series die just when we are beginning to fall in love with them. That’s not accidental, and it’s not always something you can plan either.

In the same way, the dark fringes of the show’s fandom often work their way onto the screen. The Trio, the misogynist geek villains from season 6, have a lot in common with the twenty-something fanboys who made up Buffy’s core demographic. Here is a show with the same audience breakdown as Star Trek, celebrating the efforts of a harried single mother as she battles three Star Wars-revering manchildren. They’re calling out the worst in their own fans.

But that’s what’s so magic about Buffy. It’s not always saying what I want to hear, but I always feel like it’s speaking directly to me. So for the next few months I am going to be exploring the show season by season, examining its ideas and offering some insight wherever I can. I admit up front this will not be objective. Buffy is my favorite TV show, and it’s a distant race for second. My goal isn’t to convert the curious or preach to the choir. It’s merely to celebrate a novel use of the television medium, and to remind everyone (myself included) that there are demons out there that need slaying and it’s time to get to work.

Season 1

First seasons tend to be the worst of the series. Watch any show from Breaking Bad to the Simpsons, and you’ll find the first episodes plagued by sluggish pacing, dueling priorities, and inconsistent characters. For the millions of dollars being invested, you would expect a major network TV show to be meticulously plotted. That’s not always for the best though. Consider how dry the first season of The Office is, before the writers allowed their characters to breathe outside the confines of what they thought the show needed to be. The looser, less structured product actually turned out to be much better. Or think about how great the first season of True Detective was, and compare it to the disaster of a second season. When you are telling something like a hundred hours of story, the beginning doesn’t matter nearly as much as you think.

All of this is to say that the first season of Buffy can occasionally be rough, and on a technical level it’s easily the worst of the series. The dialog is too nineties. The stories often come from clichés about high school rather than lived-in observations. The sexy older teacher turns out to be a praying mantis. When everyone’s nightmares come to life, Giles dreams about Buffy dying, Willow dreams about public speaking, and Xander dreams about being chased by a clown. At its best, it’s clever. At its worst, it’s derivative.

But for the already-converted, the first season of Buffy is a fascinating look at what might have been. Those abortive first attempts include the scariest episode the series ever produced (“The Pack”), one of the strangest episodes of television I have ever seen (“Puppet Show”), and a handful of truly great standalone Monster of the Week episodes that do the show’s predecessors (like The Twilight Zone and Star Trek) proud.

Whedon-penned “Angel” is the first episode that truly feels like the final Buffy product, beginning to end. It’s followed by the conceptual energy of “Nightmares,” a great look at loneliness with “Out of Sight, Out of Mind,” and “Prophecy Girl,” the damn-near-perfect finale that leaves no doubt this show is headed for great things.

It’s worth noting that season 1 is the sole Buffy season without any market testing. Faced with a much lower budget and faster deadlines, the Buffy team wrote, shot, and edited the entire first season before fans had even seen the premiere. The final product amounts to their best first guess. With that and the alternative blank screen in mind, it could be a lot worse.

Episodes 1 and 2 — Welcome to the Hellmouth/The Harvest

It’s your first day at a new school. Things didn’t go so well in the last town, so you’re focused on making a new start. You keep your head down in class. The popular girls want to hang out with you. A new start; a normal life; you just might be able to pull it off.

But soon enough some British librarian is asking you to continue your battle against the forces of evil, and the fate of the world is in the balance. And your allies in this battle aren’t so much the A-list as a girl so shy she can’t sustain a conversation and a dorky pop culture aficionado who has a major crush on you.

Giles isn’t alone in his premiere-closing observation, “The Earth is doomed.” At the risk of getting all big-picturey, the teens of generation X weren’t exactly considered a cultural point of pride. Raised on Saturday morning cartoons, video games, boy bands, and far more accessible porn than any generation in history, these youths, and the idea they were destined to inherit the world, unsettled many people who were a lot less uptight than Giles.

Again, I won’t argue that the first two episodes of this series are great. Clearly the whole crew was still getting their act together. The fight scenes in particular border on being unwatchable. But emotionally, this is the right foot to start on. One need only peruse a few back issues of The New York Times to see apocalyptic prophecies about Gen X that make the current Millennial backlash seem quaint. The first episode of Buffy took every teenage girl discovering the world can be a hostile place for young women, every boy who passed over his textbooks to read Spider-Man comics, every shy outcast lost in the burgeoning horizon of the worldwide web, and gave them a chance to fight and kill the ancient laws that declared they didn’t stand a chance.

And we can roll our eyes at how much The Master looks like a Power Rangers villain or how dated the pop culture references are, but still the most important quality of the entire series is apparent to those who look: we are rooting with Buffy, Willow, and Xander, because they are us. They are the attention-deficient, desensitized, undereducated problem children of a broken world, but they can still save that world the way people have done for generations.

Episode 3 — Witch

The one-word title of Buffy’s first true-blue monster of the week episode is a loaded one. Think of the first thing that comes to mind when a person says “witch.” Now think about how many of those kneejerk reactions are gross female stereotypes exaggerated into a monstrous, zeitgeist-baiting form. Buffy the slayer might have to fight a witch, but Buffy the show is clearly fighting the idea of what it means to be a witch.

Feminism (or a nineties, male showrunner version thereof) is part of the series’ DNA, but in keeping with the premiere, the allegorical demon is actually age discrimination. Someone is using black magic to sabotage cheerleading tryouts. Buffy and the gang narrow the suspects down to goth outsider, Amy. Even Buffy, despite her own struggles with identity, is quick to blame the teenage girl. The narrative paints an easy enough picture. Amy isn’t all that talented, and she doesn’t have the work ethic of the best cheerleaders. She uses dark magic to get ahead, hurting whoever she must to achieve validation she never earned.

Only that’s not quite right. Amy is only trying out for cheerleader because her mother has possessed her body and is living her own dreams through her daughter, less vicariously than literally. Amy is merely a victim of others’ expectations. It’s not the pinnacle of sophisticated storytelling, but Witch is a smart, focused look at the kinds of judgments being hurled at young people (especially teenage girls) and why those judgments are lies.

Episode 4 — Teacher’s Pet

There’s a running joke throughout the whole series about how Xander is attracted to demons. I expect an existentialist like Joss Whedon would make some comment on how men tend to be more likely to look for some kind of imagined idealization in their potential partner, while women focus more on the actual person.

And that kind of commentary does work its way into the episode. Xander admits that he watches a lot of porn, and later he blushes at the revelation that he is still a virgin. These moments feel like lived-in confessions about the confused chaos of young male sexuality. However by the standard of later Buffy metaphors, Praying Mantis Teacher is pretty uninspiring.

While Witch actually required the characters to overcome their prejudice, Xander is never actually confronted by the empty female avatars he sees in the pages of Hustler. He pursues an empty projection of his lust. He is attacked by a giant insect. It might work for Pavlov’s dog, but it really doesn’t get to the heart of the issue.

Episode 5 — Never Kill a Boy on the First Date

This episode feels like something a rookie writer would shout during the first pitch meeting. “So Buffy is on a date with a boy, but she also has to slay vampires and she has to hide her secret identity the whole time!”

Owen is the most confused of all the boys Buffy ever dated. He’s shy. He’s a little doofy to be the hunk everyone claims he is. He reads Emily Dickinson, and we all know everyone who did that in high school was super cool.

I mean I get it. Buffy has some complexity, so her dream guy probably would too. But Owen feels too much like some writer’s ideal boyfriend, as opposed to Buffy’s dream guy. As a result the whole thing turns to farce really fast, and not, as Xander might hope, the “fun, bawdy French kind.”

Episode 6 — The Pack

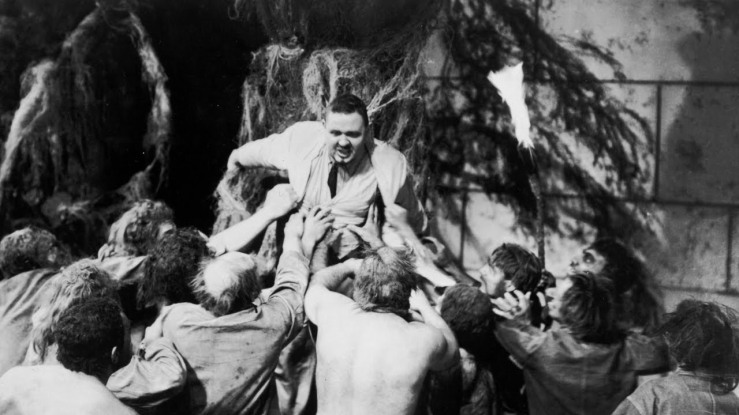

The Pack is the most frightened I have ever been that a network TV show was going to murder a baby on-screen. That’s the kind of darkness you earn. This episode isn’t exactly nuanced, but good lord is it effective. The bullies get their kicks from saying the meanest, most hurtful things they can to whoever will listen. And we must watch them eat the adorable pig mascot, cannibalize the even more adorable Principal Flutie, and terrorize the entire campus.

Two things are undoubtedly communicated here: first, there’s an inherent appeal to doing the worst possible thing. We can tell because we enjoy watching, even if we want to look away. Xander says the most hurtful thing he possibly could to a vulnerable, lovestruck Willow. And we also get to feel just how intimidating the gaze of someone who wants to hurt us can be. For a show that had 144 episodes with a monster in all of them, the scariest villain they ever concocted was a teenage boy leering down at his female victim.

Episode 7 — Angel

So let’s get into the genius of Angel for a second. The character doesn’t always work, I realize, but in the world of Buffy he is a revelation. Buffy represents the heart of a hero in the body of someone society tends to underestimate. Angel represents the opposite. On the surface Angel is the perfect person. He’s beautiful, brooding, and always around to help when evil strikes. That’s why Buffy is so surprised when he turns out to be a demon at the core.

Eventually Angel would become Buffy’s series-mate, and the larger ideas of her series would be highlighted by his contrast. Buffy is the story of a young woman learning to trust her instincts when the rest of the world is telling her who she can or cannot be. Angel is about a man who realizes he’s been allowed too much freedom–that a moment of pure happiness isn’t worth causing pain for others. While Buffy needs to reject society’s projections of her, Angel needs to learn to care more about how he affects his neighbors.

One could extrapolate too much on this. I don’t think the show is saying all men are evil and all women are inherently good. I think the looking at patterns. Men, especially straight white men, are often given free reign in society. Yet the stories told about them still tell them to pursue their own freedom at all costs. Meanwhile so many doors are closed to women, yet our narrative art remains maddeningly apathetic about their need for heroic avatars. The journey faced by women today is far more fitting for stories about heroes who learn to trust their instincts. It’s not about absolutes.

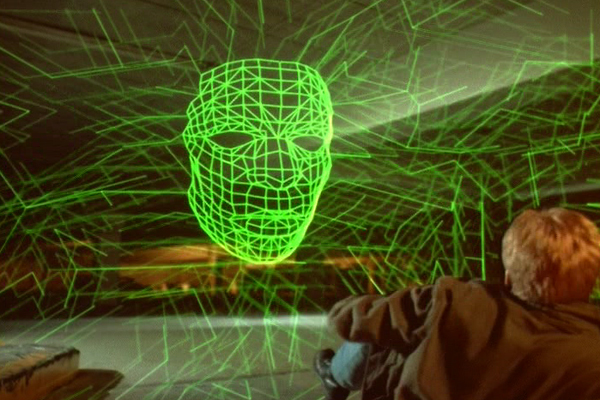

Episode 8 — I, Robot… You, Jane

It’s easy to dismiss something that just doesn’t work and not to pay attention to what the writers were trying to do. I honestly think they tried with this episode. The role of technology in society was still very much a hot button issue in 1997, not in the exact same ways it is now, but the two are comparable. Unlike sexism or bullying, it wasn’t something with a clear right and wrong. Technology was eating away at the natural enjoyment of life. We are living in a kind of dystopian realization of that fact now.

This is a Willow episode–she, after all, is Jane to the Demon Robot–but it’s also a Giles episode. From the first episode Giles served a distinct function in Buffy’s world. He is an old British man because they are the most likely people to read heroic epics. He is the archetype of all that judges the modern day by an ancient standard. Of all the characters on the show, he is the one who would not actually watch a show called Buffy the Vampire Slayer because he considers pop culture to be inherently disposable garbage that doesn’t challenge in the way fine literature does.

And while he might be underestimating the value of X-Men comics, Giles isn’t exactly wrong about computers. They did make us a less connected society. Many people operate the web in a healthy way. Many have also lost themselves. The show tries to address both sides, but they’re just not ready to tackle such a weighty topic yet. When Giles goes on his rant about how books have texture and smell, the writers (most of whom grew up in a pre-internet world) have no adequate response to give to Willow or techno-pagan Jenny Calendar. So what later seasons could maybe have pulled off as a nuanced discussion of technology in the modern world, turns into a one-dimensional “very special episode” about how online dating can kill you.

Episode 9 — The Puppet Show

I’m about to defend The Puppet Show, while admitting I’m very glad there is not another Buffy episode like it. Yes, the show succeeded with this kind of absurd genre-bender later without needing to jump off the conceptual deep end. Yes, it’s an episode in which Buffy helps a ventriloquist dummy who is really a horny demon hunter from the forties, defeat a strange alien creature disguised as a teenager who is looking to kill the puppet’s supposed owner, another teenager who has cancer. Also apparently Giles is judging the talent show and Buffy, Xander, and Willow have to perform a scene from Oedipus.

But if a person dreamed a Buffy episode, it would probably look a lot like this. The elements that make the show coherent are amplified here more than in the focused, more intelligent episodes. You’ve got the burgeoning camraderie of Buffy, Xander, and Willow, the playful relationship Giles has with his teenage counterparts, the absurd Scooby action amplified for maximum campiness. There’s a point I will raise later in season 3, about how every great show eventually becomes a parody of itself because the most powerful joke is an inside joke. This is the first time Buffy the series views itself as an inside joke. It’s not consistent, but also there’s Willow running off stage to throw up in the middle of an Oedipus monologue.

So you lose some, you win some.

Episode 10 — Nightmares

I hope you’ll forgive me, but I’m going to draw another comparison to Community. Nightmares has a lot in common with that show’s signature episode, Modern Warfare. It’s not revered by fans in the same way, nor is it nearly as good an episode of television. However this does have one very important thing in common with that paintball action movie pastiche: both episodes represent the moment their shows destroyed all their boundaries.

Dan Harmon likes to talk about how Modern Warfare was the first moment he saw Community as a show he loved as well as worked on. By making their show a parody of the tropes of other media, Community established that they could go anywhere and do anything that captured their imagination. “Nightmares” does something similar. It’s the first instance of Buffy’s writers embracing their “emotions as magic” motif and letting it wreak havoc on the world they constructed.

The magic here is nightmares. Everyone has them. And by episode 10, fans had a chance to identify with the characters and see how they constructed their world. The nightmares aren’t all that unique (as I mentioned earlier) but still there’s a thrill to seeing Buffy, Giles, et al face the same problem. And when the writers got the chance to keep what worked in season 2, they kept returning to the outline of this episode. Just like “Modern Warfare” bore classics like “Advanced Dungeons and Dragons” and “Critical Film Studies” in its DNA, “Nightmares” foreshadows Buffy classics like “Hush,” “Once More with Feeling,” and even “The Body.” We take an emotion or type of magic. We filter the lives of all the characters through that prism and see how they respond. How would all the characters behave if their darkest secrets came out in Broadway-style musical numbers? How would they act if none of them could speak? How would they react to a real-world death?

It’s the moment a show goes from telling the audience something to asking, “What if?” alongside everyone else. That’s the moment a story becomes capable of anything.

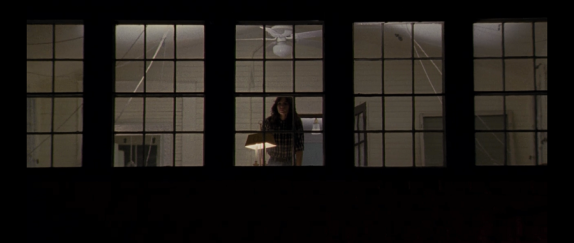

Episode 11 — Out of Sight, Out of Mind

Along with The Pack, this is one of the episodes that defines Buffy’s first season as its own valuable entity. Both stories are very rough in places, but they also show the careless cruelty and psychological confusion of high school life in ways later seasons shied away from. Here a girl named Marcy is ignored so much she turns invisible. She uses her newfound curse/power to haunt Cordelia, the most popular girl in the school.

The turning point comes when Marcy finally gets Cordelia tied up in a chair. A lot of high school shows, especially in the nineties, glorified the loners and ragged on the oppressive bourgeois class. Buffy took it one step farther. Marcy gets the chance to pursue her bitterness. She gets her supposed enemy tied up. But then what? By taking jealousy to its natural conclusion, the show begs the question: what’s the point of going down that path in the first place? What are we glorifying when we mindlessly attack those we perceive as more loved or valued than we are? Are we really willing to follow that to its natural conclusion?

That’s something you can say out loud. Or you can watch the knife rub back and forth across Cordelia’s face as Marcy prepares to push her pain on another person.

Sidenote: this is also the first episode where Cordelia makes sense as a character.

Episode 12 — Prophecy Girl

What does it mean to die metaphorically? Writers, especially screenwriters, love to cite big story charts with Joseph Campbell’s name plastered all over, in which a hero journeys into the unknown, faces death, and emerges with newfound strength and wisdom. Every story, they will tell you, is really about death.

That’s all nice and poetic, but what does it really mean? To end its first season, Buffy explores the meaning of heroism and does its best to elaborate on why all this pseudo-intellectual, metaphysical psycho-babble actually matters. The episode begins with Buffy being told she is going to die. Unlike other prophecies and negative preconceptions, this one is absolutely, for sure going to come true.

Later Buffy finales would deal more specifically with the real challenges of being a teenager. She would fight against the dark side of love, the abuse of authority, threats against her family and her way of life. But to end its first season, Buffy has to bring everything full circle. Buffy has earned the respect of her British Harold Bloom avatar. She has forged her own path in the social Darwinism of high school. She defeated her foes and looked good doing it. But now she must prove that she can face the oldest, most powerful force in human life. Like Odysseus, Aeneas, Beowulf, and Neo before her (or, I guess in Neo’s case, two years after her), she must pass through the threshold of certain death.

Understandably she has reservations. It’s not fair. It shouldn’t be necessary for a happy, healthy life. And looking at her face, even Giles can’t help but agree. But this is where the genius of Buffy comes in. Anyone with a $30 Barnes and Noble gift card can learn all about how to write stories about life and death. But it takes real talent to identify where we face similar thresholds in our everyday lives. Xander knows Buffy will reject him, but he asks her out anyway. Willow loves Xander and feels pressure to assent to everything he says, but she chooses not to be his backup because she knows it will make her miserable.

And ultimately a similar ordinary life story inspires Buffy to face down the dark lord of the vampires and save the world. Joyce gets her best moment of the series in which she’s not a dead body, recounting a night she went stag to a dance and wound up meeting Buffy’s father. In the midst of certain failure, she found her victory. So Buffy puts on her best dress, grabs her crossbow, and walks through death to save the world.

And the definitive touch is just how absurd it all seems. The Master kills Buffy. Xander revives her. She wakes up with a newfound confidence and kicks ass. There’s no real reason to this change. Honestly, it’s impossible to explain logically. Why does it work that way? Why must we pass through our greatest fears, our most certain failures, in order to find happiness? Aliens in the audience might find it the ultimate kind of farce. You only know it’s true if you’ve experienced it before, which every human being has the potential to do.